I like books for two reasons. The first is the obvious one. I love to read them. The other, though, is the same reason that acts as brake to any impetus ever pushing me toward the ever-more popular e-readers. That is I love to HAVE them. Certain books look and smell and feel differently from others. When I was a kid, I picked up and bought a book at our grade school's annual Bookfair just because I liked the way it looked and felt. I never did read the stupid thing.

Tonight, feeling a little guilty (not enough to do much about it) about not tackling the massive and highly anticipated--by me--pontification on Hulme, I went to my bookshelves to look for a poem. It's Sunday, after all, and this is the first weekly entry for

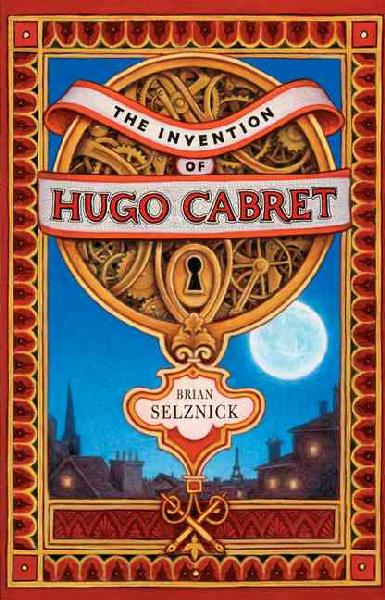

Sunday Poetry. I wanted to choose a poem that was, you know, "just right" for the first of the series. On a whim, I picked up a little book a lot like that book I grabbed at that old Bookfair:

The Hoosier Book of Riley Verse, collected and arranged by Hewitt Handson Howland on behalf of James Whitcomb Riley.

The book is ancient. It smells of dust and ink. It's printed on that old "onion skin" paper, and has the same pretentious mottled gold along the three edges of the closed pages as do my various Oxford publications and my scriptures. It is falling apart. BUT, there is that particular SOMETHING about it that makes it a pleasure to hold and to touch. It is heavy for its size--heavy they way you hear the produce man in the grocery store describe the best tomatoes or cantaloupes.

I don't know a thing about J.W. Riley, but very surprised nonetheless when, an hour or so ago, I read Mr. Howland's introduction to the collection, and, as it turns out, Riley felt the same way about his books:

"When James Whitcomb Riley was a very small boy, too young to read, he fell in love at first sight with a book, and like all intense lovers he at once desired to possess the object of his affection. By thrift and careful hoarding he got together pennies equal to the price, and the little red and gold 'poetry book' fell into his eager, outstretched, freckled hands.

"Now he did not love this early treasure for what it contained, but for its look, for the feel of it in his hand, as he afterward said."

I don't even know where I got this book (a pretty rare thing for me, especially considering my most usual bookmark is the receipt of the book's purchase), but I know I kept it for its look and feel. I suppose once upon a time I even flipped through it. I must not have been all that impressed, because I don't know for sure if I actually ever looked inside or not (I just hate to admit that I bought a book that I didn't even open!).

Now I'm glad I've revisited it. The poetry is a riot of colloquial humor, wisdom, nonsense, and love, all particular to this poet's varied heritage. (When I wikipedia'd him--typed his name into the engine and waited the .834-whatever second for the entry to pop up--I expected a short blurb with birth and death dates and maybe a bibliography. Holy crap, was I wrong! BIG entry. This was some man.

Check him out.)

To give you an idea of the poetry--or "verse," it says of itself without airs--here contained, a few of the section titles, whose poems--yes POEMS!--are reminiscent of some crazy cross between Uncle Remus, Shel Sylverstein, John Keates (go ahead and call me out on this; I will defend!), and Pablo Neruda:

- NEIGHBORLY POEMS

- AFTERWHILES

- PIPES O' PAN AT ZEKESBURY

- POEMS OF CHILDHOOD

- THE ARMAZINDY

- HOME-FOLKS

As for the poetry itself, I don't want to spoil it with analysis. Here, then, are three, which I think are just great:

Jack the Giant Killer

Bad Boy's Version

Tell you a story--an' it's a fac':--

Wunst wuz a little boy, name wuz Jack,

An' he had a sword an' buckle an' strap

Maked of gold, an' a "'visibul cap";

An' he killed Gi'nts 'at et whole cows--

Th' horns an' all--an' pigs an' sows!

But Jack, his golding sword wuz, oh!

So awful sharp 'at he could go

An' cut th' old Gi'nts clean in too (sic)

'Fore 'ey knowed what he was goin' to do!

An'

one ole Gi'nt, he had four

Heads, and name wuz "Bumblebore"--

An' he wuz feared o' Jack--'cause he,

Jack, he killed six--five--ten--three,

An' all o' th' uther ole Gi'nts but him:

An' thay wuz a place Jack haf to swim

'Fore he could git t' ole "Bumblebore"--

Nen thay wuz "griffuns" at the door:

But Jack, he thist plunged in an' swum

Clean acrost; an' when he come

To th' uther side, he thist put on

His "'visibul cap," an' nen, dog-gone!

You couldn't see him at all!--An' so

He slewed the "griffuns"--

boff, you know!

Nen wuz a hurn hunged over his head,

High on th' wall, an' words 'at read,--

"Whoever kin this trumput blow

Shall cause the Gi'nts overth'ow!"

An' Jack, he thist reached up an' blowed

The stuffin' out of it! an' th'owed

Th' castul-gates wide open, an'

Nen tuk his gold sword in his han',

An' thist marched in t' ole "Bumblebore,"

An', 'fore he knowed, he put 'bout four

Heads on him--an' chopped 'em off, too!--

Wisht 'at

I'd been Jack!--don't you?

***

Name Us no Names no More

Sing, oh, rarest of roundelays!--

Sing the hilarity and delight

Of our childhood's gurgling, giggling days!

When our eyes were as twinkling-keen and bright

And our laughs as thick as the stars at night,

And our breasts volcanoes of pent hoo-rays!

When we grouped together in secret mirth

And sniggered at everything on earth--

But specially when strange visitors came

And we learned, for instance, that their name

was Fishback--or Mothershead--or Philpott--

or Dalrymple--or Fullenwider--or Applewhite--

or Hunnicutt--or Tubbs--or Oldshoe!

"'Oldshoe!'--jeminey-jee!" thinks we--

"Hain't that a funny name!--tee-hee-hee!"

Barefoot races from everywhere,

We'd pelt in over the back porch floor

For "the settin'room," and cluster there

Life a clot of bees round an apple-core,

And sleeve our noses, and pinafore

Our smearcase-mouths, and slick out hair,

And stare and listen, and try to look

Like "Agnes" does in the old school-book,--

Till at last we'd catch the visitor's name,--

Redinhouse, Lippscomb, or Burlingame,--

or Winkler--or Smock--or Tutewiler--or

Daubenspeck--or Throckmorton--or Rubottom

--or Bixler--

"'Bixler!' jeminy-jee!" thinks we--

"Hain't that a funny name!--tee-hee-hee!"

Peace!--Let be!--Fall away!--Fetch loose!--

We can't have fun as we had fun

then!--

Shut up, Memory!--what's the use?--

When the girls and boys of 8 and 10

Are now--well,

matronly, or

old men,

And Time has (so to say) "cooked our goose!"

But ah! if we only

could have back

The long-lost laughs that we now so lack

And so vainly long for,--how--we--

could

Naturely wake up the neigh-ber-

hood,

over the still heterogenious names ever un-

rolling from the endless roster of ortho-

graphic actualities,--such names--for fur-

there instance of good faith--simply such

names as Vanderlip--or Funkhouser--or

Smoot--or Galbreath--or Frybarger--or

Dinwiddie--or Bouslog--or Puterbaugh--

or Longnecker--or Hartpence--or Wig-

gins--or Pangborn--or Bowersox--

"Bowersox"! Gee!--But alas! now we

Taste salt tears in our "tee-hee-hee"!

***

The Youthful Patriot

O what did the little boy do

'At nobody wanted him to?

Didn't do nothin' but romp an' run,

And whoop an' holler an' bang his gun

An' bu'st fire-crackers, an' ist have fun--

An'

'ats' all the little boy done!

***

The Hoosier Book of Riley Verse, by James Whitcomb Riley,

collected and arranged by Hewitt Hanson Howland,

published in Indianapolis by The Bobbs-Merrill Company Publishers,

copyright 1916.