Some people are naturally trusting; some people are naturally suspicious. Most commonly, these congenital characteristics are most pronounced (at least so I've concluded as based upon my ten years' observations as a teacher) when confronted with authority. I, myself, happen to be of the trusting disposition. Despite this what-some-may-cruelly-call weakness, however, I have trained myself over time to harbor suspicion against one authority in particular: dictionaries.

Say it with me:

DICTIONARIES

Naturally, dictionaries are uncommonly authoritative. Just their presence intimidates. Opening and searching their pages are in and of themselves acts of submission. We, as a species, blindly assume that Dictionary (intentionally applied omission of either definite or indefinite articles) is always right, and that those who contradict it are idiots, unworthy of our consideration. Well, only if the one who hasn't submitted to Dictionary isn't

us and only if we have actually already submitted ourselves to Dictionary's overwhelming greatness and committed ourselves to its mastery.

Baloney (...or bologna.) --and just forget it if two dictionaries contradict

each other, which is, of course, the whole point

|

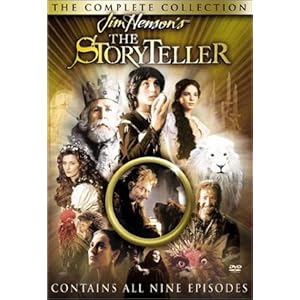

| some of my dictionaries |

Despite my suspicions and disillusionment, I am an avowed Dictionary lover (for the sake of specificity, I will now shift away from my use of Dictionary to the more accurate, and appropriately less fawning,

dictionaries; I have a lot of them, after all, and their differences are their greatest strengths!), so what I'm about to write may

shock you, and all the more so if you happen to be one who

doesn't own a dictionary or happens only to own one dictionary (which tome is likely dusty, neglected, and sadly uncracked), or you only use--heaven forbid! --the

internet (hypocrisy admitted) for your references--and worst still if you only ever use

just one site (and if any of this sentence applies to you, then

squint your eyes and defensively shrug your shoulders):

DICTIONARIES ARE NOT ALWAYS RIGHT.

Need me to say it again?

DICTIONARIES ARE NOT ALWAYS RIGHT!

It's a lot like when I was in 7th grade and my teacher, for the first time in his existence-known-to-us, was late, and when he finally arrived he leaned casually in the door and waited until he had everyone's attention--even made eye contact with every single student in the room, one by one--and then, calmly, yet with clearly ill-suppressed glee, said the single word, and in all caps: "SEX." Mind you, this was 1989 in a little conservative town in Ohio, and I think half the students in the room fainted--seriously: just fell right "out they chairs"; and the other half spent the next several minutes catching their collective breath. None dared speak or utter question! The shock of it!! (

Sex??)

Well, the above statement--centered and reddened--may be a little like the doorway dictum of my 7th grade pre-algebra teacher: verily,

dictionaries are not always right; in fact, they are often wrong. Why else do you think there are so many of them out there? Every publisher thinks he can create a better assemblage of the English lexicon than all the others.

Unfortunately, woe betide me, I don't have a mountain of examples of such errors or shortcomings. Though I stumble upon them regularly, I've never kept track. That changes TODAY! (It's like the years I worked for BYU Information, giving out phone numbers and information for staff, students, and departments and connecting calls, etcetera and I came across SO MANY crazy names, but I never kept track! How sad! Now, despite the dozens and dozens of quirky names I ever encountered, all I remember is the listing for one unfortunate student: Mr. GAMBLE LYNN MONNEY. Yes. Two Ns.)

What drew my attention to this, my lack of gathering and amassing, was one of today's posts at The Language Log. Read it

HERE. Webster's dictionaries, which I've found are the ones most likely to disappoint (but don't get me wrong: they has their uses, and some more than that of kindling; and, yes, I even own one -- ultimately it's all about using the right dictionary for the right job, or better, using several dictionaries in tandem (and if you're curious what a dictionary's actual job is, look

it up!; and if you've got lots of time, read

The Professor and the Madman, which I've recommended before), is taken to task here for its inadequate definition of "passive," as it relates to English grammar and syntax. Mark Liberman, who wrote the essay, takes the time to repair the misconceptions, about which I--yes, the English teacher--have had my own questions and failures. His instruction is welcome, concise, and entertaining. I recommend it (not to mention the entire "log"), and all the more so because the post makes it quite clear that teachers and professors are a lot like dictionaries. (Yes, again: this from a teacher.)

They're often wrong.

Raise your hands if you've ever found penciled or, worse,

red-penned on your hard-done paper recently returned from Professor So-and-So or Mr./Ms./Miss/Mrs. So-and-So the words "PASSIVE SENTENCE -- PLEASE FIX." All of you? (Okay, if you've never written a passive sentence, then you don't count; stop reading ... well, unless you're willing to repent and change your ways.) Guess what: most likely they're wrong! And best of all, they don't know they're wrong and would likely never admit they're wrong.

How do I know?

Teacher.

And why would you tell them, when you can relish in your rightness, their wrongness? Trust me: don't explain it to them. Ninety percent of them wouldn't get it anyway :: Websterians all!

Again, how do I know? How can I be so sure? Yes, I am a teacher. Worse, I have been that very teacher who accuses and demands correction without fully understanding the issue. I'm sorry. And the dictionaries didn't help me. Trust me; I looked.

If I'd only used more than one together....

Sorry.

So just like using the right dictionary and better and again,

multiple dictionaries, really knowing your active/passive "voice" gives you a one up on your teacher--a reason to feel superior to those around you, most importantly of whom may very well be your teachers/professors, and which superiority SHOULD NEVER BE DISCLOSED. Remember, only another in-the-know like you will understand and not disbelieve everything you say. And let's face it, if they get it too, well, what's the point in showing off?

Read Liberman's article, buy a few extra dictionaries, and

live.